More than just the blues

Why talk about Postpartum Depression? In the last few years, I’ve had friends and clients that have suffered from this illness and were completely shocked. They felt underprepared and as if the medical system they came into contact with just ‘glazed over’ the issue. The feeling is that many people in the industry just don’t want to ‘scare people’. Isn’t it scarier being in the middle of it and feeling all alone?

It’s Okay

As with all of my work with depression, my goal is to destigmatise it. Everyone should know about this, so that it becomes okay to talk about it, okay to have suffered with it and okay to ask for help. If you agree, please share this article so more women can be aware for their own health.

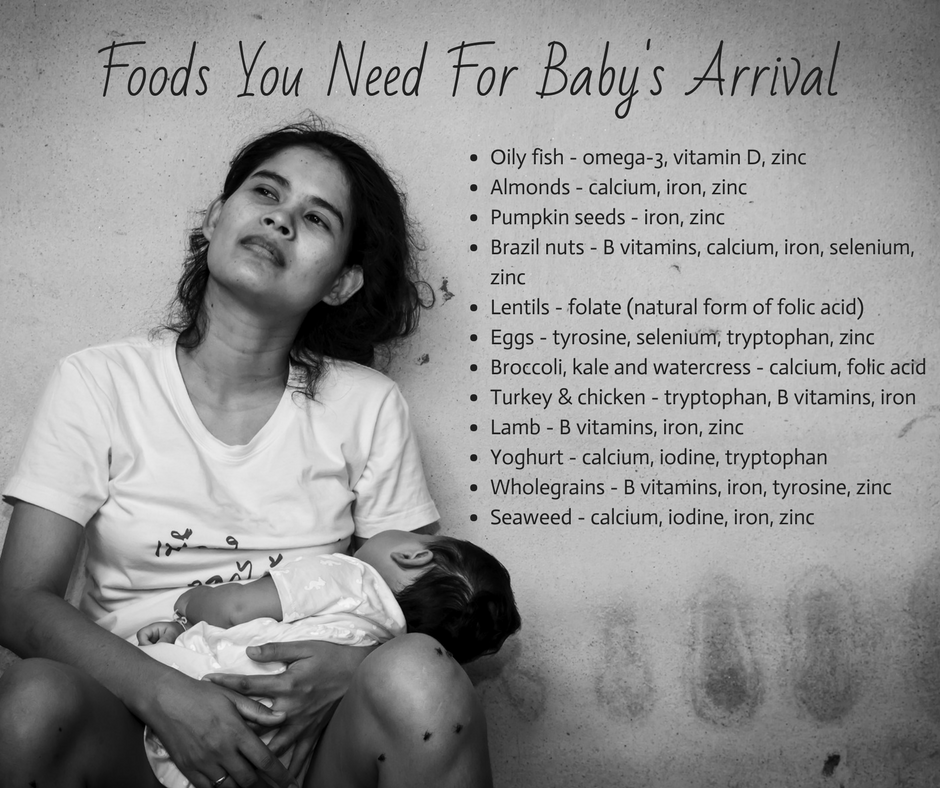

QUICK NOTES: If you don’t have time to read the entire post, skip to the images, which have lots of info on them and the section on ‘How do you Recognise When it’s not Just the Blues?’. You can also get a lighter version on the podcast ‘Mums’s the Word’. Read this Real Life interview with a mum who shares her experience of postpartum depression.

What is Postpartum Depression?

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a depressive state that can occur after giving birth. Some refer to it as post natal depression (PND). Some people call it the blues, but this is not entirely correct and we should define it a bit more clearly as three different possible states:

Postpartum blues; ‘the blues’ as it is sometimes called, refers to a healthy range of sadness that reaches a peak around 5 days after giving birth and then tends to resolve itself within two weeks. Severe postpartum blues may also occur.

Postpartum depression; which may occur when the postpartum blues have been particularly severe, is a more severe depression.

Postpartum psychosis; is a more extreme, but rare, mood disorder. This particular post does not cover this topic.

The Stats

Postpartum blues occur in around 75% of women.22 A fewer number experience severe postpartum blues, which leads more frequently to PPD. The percentage of women who are treated for PPD is 13%, however the numbers show that up to 20% experience high enough scores to fall under the description of having PPD15-17. It may be experienced up to a year following the birth of your child, however, the highest incidence happens within 2-3 months after birth2. It is more of a postpartum risk than gestational diabetes (3-8%)18 and pre-term birth (12.3%)19.

Are You at Risk?

What you really want to know is, are you at risk? Being at risk of developing PPD does NOT mean you’re going to have it. Rest assured, it only means you may be more likely to develop it than your friend down the street. PPD can affect anyone, whether they are considered a low risk, or a high risk person. These are some of the situations where you may want to ensure you have extra support before, during and after your pregnancy:

Current mood disorders

Do you suffer from depression or anxiety at the moment or does one of your family members? Research shows that there is a possibility of experiencing some kind of post natal depression

Have you had PPD during a previous pregnancy?

This may increase the chance that it happens in a later pregnancy, but is not a guarantee

Chronic stress

or any major stressful event has happened before or during your pregnancy such as the death of a loved one or divorce

Support network

A lack of strong emotional support from a partner, family or friends

Thyroid function

Hypo- or hyper-thyroid function or where there are high levels of thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO-ab) during pregnancy10

Age

Are you 20 years old or younger? This may mean you are more vulnerable to PPD11

How is it diagnosed?

If you suspect that you, or a friend or relative, may be suffering with PPD you should have your GP involved to make an assessment. The Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) is a widely accepted questionnaire that is used to identify postpartum depression and The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) helps identify severity. It would then be followed up by a clinical diagnosis.

How can YOU Recognise When it’s not Just the Blues?

(source is from the Mayo Clinic)

Postpartum Baby Blues

This can last from a few days up to 2 weeks and are a normal process. You may be experiencing it if you have the following symptoms:

- Mood swings

- Anxiety

- Sadness

- Irritability

- Feeling overwhelmed

- Crying

- Reduced concentration

- Appetite problems

- Trouble sleeping

Postpartum Depression

If these symptoms persist or increase in intensity and interfere with your daily life or ability to care for your baby then you may be experiencing PPD. Symptoms may last for many months or longer and include:

- Depressed mood or severe mood swings

- Excessive crying

- Difficulty bonding with your baby

- Withdrawing from family and friends

- Loss of appetite or eating much more than usual

- Inability to sleep (insomnia) or sleeping too much

- Overwhelming fatigue or loss of energy

- Reduced interest and pleasure in activities you used to enjoy

- Intense irritability and anger

- Fear that you’re not a good mother

- Feelings of worthlessness, shame, guilt or inadequacy

- Diminished ability to think clearly, concentrate or make decisions

- Severe anxiety and panic attacks

- Thoughts of harming yourself or your baby

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide

Postpartum Psychosis

This is much more serious than the baby blues, but is rare. The symptoms and signs include the following:

- Confusion and disorientation

- Obsessive thoughts about your baby

- Hallucinations and delusions

- Sleep disturbances

- Paranoia

- Attempts to harm yourself or your baby

What Causes PPD?

There are several current theories that include an imbalance of steroid hormones (sex hormones), glucocorticoids (cortisol) and oxytocin. More recently, research has included inflammation, HPA axis dysfunction, epigenetics and more. Here’s a brief description of these:

Dramatic hormonal changes occur postpartum.

Oestrogen levels drop by around 100 times in the first two days after giving birth. Progesterone (and allopregnanalone) also drops significantly and are considered to contribute to the ‘baby blues’. Allopregnanolone tends to be low postpartum and is linked to a raised incidence of depression. It is broken down from progesterone and modulates GABA receptors. This means that it protects the brain and its growth as well as how we deal with stress.25

Stress and the HPA axis are intimately linked to depression.

Glucocorticoids, such as cortisol, are raised during stress and are controlled by the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland in the brain. In people suffering with depression, there is a malfunction in the system that would normally lower cortisol. This results in anxiety, tearfulness and agitatation. High levels of cortisol may lead to reduced cell growth in the hippocampus of the brain, which can affect memory. These hormones may also be increased due to the changes in pregnancy hormones.1

Women at risk for PPD have been found to have lower oxytocin,

however injection doesn’t always lower the incidence of depression. Additionally, oxytocin interacts with coritsol and may lower mood, although in rat studies it shows positive results.1,23 Research is still needed in this area.

Epigenetic mechanisms like histone modifications and DNA methylation.

You can read more about what epigenetics are following the link above.

The inflammation

hypothosis is supported by many studies that found raised levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in depressed patients.37-38 Chronic inflammation (with long periods of raised pro-inflammatory cytokines) may trigger a depressive episode.39-40 What cytokines do is prevent the amino acid tryptophan from converting into serotonin. They also divert tryptophan into kynurenine, which then converts into neurotoxic quinolinic acid.41,42 Supplementation of niacin (vitamin B3) may prevent kynurenine production and is especially important if taking anti-depressants.43-45

What we notice in PPD

- Post partum, the plasticity of the brain (hippocampus) is reduced and this may also contribute to the possibility of suffering from PPD.

- Monoamine oxidase (MAO-A) increases by the 4th day postpartum.11 The predominant theory in the medical world is that it lowers the production of neurotransmitters such as serotonin. There is criticism about the limitations of this theory, as there is good evidence that other factors are also involved. It may increase in response to the decrease of oestrogen and progesterone.20

- Glutamate increases (excitatory) and can contribute to anxiety.

- Women who breastfeed tend to have lower levels of PPD.21

Prevention & Care

Top Strategies When Dealing with PPD

Your GP may recommend anti-depressants following a diagnosis. This article does not cover anti-depressants and any recommendations here should be checked for interactions with any medication you are taking. This can be done with your Nutritional Therapist, Naturopath, GP or therapist. Some research does indicate that medication treatment may be enhanced if you are also getting hormonal support.3

1. Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Essential fatty acids (EFAs) are important for the structures and functioning of the nervous system and brain. They also regulate immune function, improve blood flow in the brain and reduce inflammation.5,9 A mum’s intake of EFAs is essential for the baby’s brain and nervous system and the production of breast milk, especially as stores tend to decrease as the pregnancy progresses.6 Consumption of seafood has been linked to low levels of PPD and a small, open trial demonstrated that levels of depression were reduced with supplementation of EFA and DHA, two omega -3 fatty acids.7,8

2. B Vitamins

In order to produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin, melatonin and dopamine the body needs vitamins B6, folate (B9) and B12. Folate and B12 are also involved in reducing neurotoxic levels of homocysteine and folate deficiency may also increase MAO-A.26

3. Vitamin D

Not really a vitamin, vitamin D behaves more like a hormone. It protects the brain (neuroprotective) and lowers inflammation and boosts mood.27

4. Calcium

Due to a baby’s calcium requirements for building bones, they may leave the mother at risk of deficiency during pregnancy. Calcium plays a role in neurotransmitter release and has shown to reduce postpartum depression after 3 months of supplementation.28 PMS symptoms were found to respond to both calcium and vitamin D supplementation.29

5. Iodine

Iodine is required for brain development during foetal and early postnatal life and also for breastfeeding. Therefore, the mother’s requirements also increase during and post pregnancy… by about 50%. This is in part due to the increased activity of the thyroid and need for nutrients that support the thyroid.30,31

6. Iron

It’s thought that more than 50% of women of reproductive age are low in iron, resulting in irritability, poor concentration, fatigue and apathy.32 Stress scores were found to reduce with iron supplementation and women with iron anaemia postpartum may be at higher risk of PPD.33 A deficiency in iron may also reduce thyroid hormone levels and alter how the thyroid functions.34

7. Selenium

This mineral plays an important role in the synthesis and break down of thyroid hormones as well as immune function and therefore has an effect on mood. Selenium is an important component of the very powerful antioxidant glutathione.5

8. Zinc

The mineral zinc, which can be found in every cell in the body, is related to the severity of depression in PPD.35 Low zinc and increased inflammation have both been alleviated by zinc supplementation.36 Zinc is also required to produce serotonin, dopamine and melatonin.

9. Tyrosine

This amino acid is involved in the synthesis of dopamine. Dopamine is a molecule that helps increase attention and learning and is activated in response to humour, social interaction and food.

10. Tryptophan

Tryptophan is an amino acid that converts into the neurotransmitters serotonin and melatonin. It has been found to be deficient in pregnancy and also with major depression and inflammation.12 A drop in serotonin five days after birth (peak time for the blues) has been observed and may be involved in the development of depression.13

11. Turmeric

The active ingredient in turmeric is called curcumin or Curcuma longa. In addition to its anticancer, antiviral and antiarthritic and antioxidant properties, turmeric is also anti-inflammatory.46 It has been found to lower inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6) and transcription factors (NFkB) and protein kinases.47-48

12. Exercise

We’ve heard it many times before, but exercise is important for our health and may reduce depressive symptoms.24 By moving around, you increase the blood flow to your brain and areas of your body that need to recover. Take your baby for a walk to give you both fresh air. This may help them sleep and can distract you. Take it easy at first, especially if you tore or had an epesiotomy. In the beginning, you can do some simple stretches like these, these or these.

13. Complementary therapies

In addition to nutritional therapy there are other therapies that have been shown to help some people with PPD and depression during pregnancy. Acupuncture, massage and light therapy are some areas to start on and you can ask in your local mother groups for recommendations.

14. Rely on your network!

Research shows that regular contact and support goes a long way towards recovery. Ask your friends to take turns coming by to check on you or ask your family members to stay with you for a few days, or a week at a time to help out or reach out to support groups. These could be official governmental groups or a local mamas group like Amsterdam Mamas.

15. Daily contact with your midwife, doula or prenatal nurse.

Your medical team are there to support you and can help you get support. Expecting someone on a daily basis can help lift the weight of being on your own with a new baby.

16. Psychotherapy

Speaking with someone impartial means you can share the frustrations and other feelings that you have about your new situation. Psychologists have skills they can teach you and help you identify coping skills for yourself.

17. Be patient with yourself

Rome wasn’t built in a day. Breast feeding may not come easily to you. Sometimes getting out of bed is difficult. You need to take care of you and know that your recovery will be different to someone else’s. Comparing yourself to others is like comparing apples and oranges; you are unique! Your recovery will be unique too so be gentle on yourself.

If you found this useful, or know someone who would, please share it with them using the links below. If you would like a free 15 minute telephone consultation to explore the nutritional possibilities, you can book here.

- Postpartum depression: Etiology, treatment and consequences for maternal care

- Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence

- Effectiveness of antidepressant treatments in pre-menopausal versus post-menopausal women: a pilot study on differential effects of sex hormones on antidepressant effects.

- Beyond the monoaminergic hypothesis: neuroplasticity and epigenetic changes in a transgenic mouse model of depression.

- Nutrition and Depression: Implications for Improving Mental Health Among Childbearing-Aged Women

- Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence basis for treatment and future research in psychiatry.

- Seafood consumption, the DHA content of mothers’ milk and prevalence rates of postpartum depression: a cross-national, ecological analysis.

- An open trial of Omega-3 fatty acids for depression in pregnancy.

- Health benefits of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid.

- Thyroid peroxidase antibodies during early gestation and the subsequent risk of first-onset postpartum depression: A prospective cohort study.

- Patterns of Perinatal Depression and Stress in Late Adolescent and Young Adult Mothers.

- Effects of pregnancy and delivery on the availability of plasma tryptophan to the brain: relationships to delivery-induced immune activation and early post-partum anxiety and depression.

- Sequential serotonin and noradrenalin associated processes involved in postpartum blues.

- Elevated brain monoamine oxidase A binding in the early postpartum period.

- Postpartum Depression.

- Preventing postpartum depression: Review and recommendations.

- Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings.

- Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) over time and by birth cohort: Kaiser Permanente of Colorado GDM Screening Program.

- An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood.

- Selective dietary supplementation in early postpartum is associated with high resilience against depressed mood.

- Hormonal aspects of postpartum depression.

- Nutritional Therapy for Postpartum Blues Might Be Effective.

- Injection of oxytocin into paraventricular nucleus reverses depressive-like behaviors in the postpartum depression rat model.

- Does aerobic exercise reduce postpartum depressive symptoms? a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- The role of allopregnanolone in depression and anxiety.

- Folate, vitamin B12, and neuropsychiatric disorders.

- Neurosteroid hormone vitamin D and its utility in clinical nutrition.

- Prenatal calcium supplementation and postpartum depression: an ancillary study to a randomized trial of calcium for prevention of preeclampsia.

- Effects of calcium supplement therapy in women with premenstrual syndrome.

- Iodine Nutrition in Pregnancy and Lactation.

- Thyroid dysfunction and women’s reproductive health.

- The prevalence of anaemia in women.

- Maternal Iron Deficiency Anemia Affects Postpartum Emotions and Cognition.

- Low Hemoglobin Level Is a Risk Factor for Postpartum Depression.

- Antepartum/postpartum depressive symptoms and serum zinc and magnesium levels.

- Zinc: The New Antidepressant?

- Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1β, tumour necrosis factor α and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder.

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines and treatment response to escitalopram in major depressive disorder.

- So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from?

- Inflammatory cytokines in depression: neurobiological mechanisms and therapeutic implications.

- The immune-mediated alteration of serotonin and glutamate: towards an integrated view of depression.

- Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and immune changes under antidepressive treatment in major depression in females.

- Tryptophan metabolism, from nutrition to potential therapeutic applications.

- Increase in conversion of tryptophan to niacin in pregnant rats.

- Antidepressants may lead to a decrease in niacin and NAD in patients with poor dietary intake.

- Curcumin: an orally bioavailable blocker of TNF and other pro-inflammatory biomarkers.

- Targets of curcumin.

- Discovery of Curcumin, a Component of the Golden Spice, and Its Miraculous Biological Activities.

Comments

[…] that, it’s so important to keep eating well. So ask those who love you to read this post on Postpartum Depression and skip to the image that tells you what foods to prepare to keep you […]

[…] https://joycebergsma.com/postpartum-depression/ […]